Two rare books were just auctioned at Christie’s, one by Johannes Kepler, Phaenomenon singulare seu Mercurius, 1609, advertised as a “Rare Kepler Mistake”, and a second one, presented as “Galileo endorses Copernicus”, Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari e loro accidenti, 1613, a first edition of Galileo’s published endorsement of the Copernican model, both works coming from the Astronomical Library of the late Owen Gingerich, a Professor of Astronomy and History of Science at Harvard University.

Together they provide a beautiful example of what was then the early stages of the scientific method, science’s methodology for progress and accumulation of knowledge, and the power of visual imagination.

Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei were contemporaries, and key figures, in astronomy in the 17th century.

Kepler produced the Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, describing the orbits of planets around the Sun and showing that planets have elliptical orbits. His work greatly influenced Isaac Newton who was able to show that Kepler’s Laws emerged as consequence of his theory of universal gravitation.

Galileo’s achievements were simply extraordinary; he conclusively proved the existence of craters on the Moon, discovered the moons of Jupiter and, more than anybody else, is responsible for the emergence of Newton. Of Galileo Stephen Hawking said, “…perhaps more than any other single person, was responsible for the birth of modern science.”

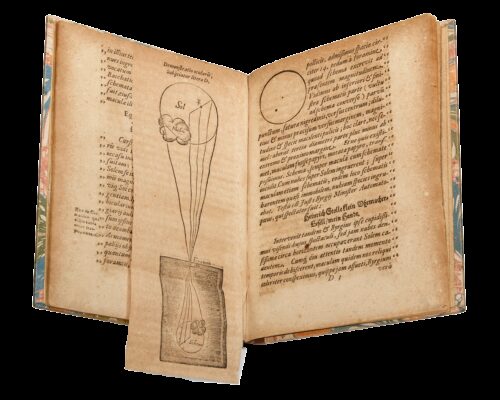

On the 28th of May 1607, Kepler observed the Sun by letting its light pass through a tiny aperture in a darkened room. With this method, what is known as camera obscura or pinhole camera, he observed a small black dot passing over the Sun’s surface, which he believed to be the motion of the planet Mercury. He published his observations in the volume auctioned by Christie’s.

KEPLER, Johanes (1571-1630). Phaenomenon singulare seu Mercurius in Sole.

Leipzig: printed by Tobias Beyer for Thomas Shurer, 1609. Kepler observed the sun

by letting its light pass through a tiny aperture in a darkened room. The folding plate

depicts Kepler’s camera obscura apparatus.

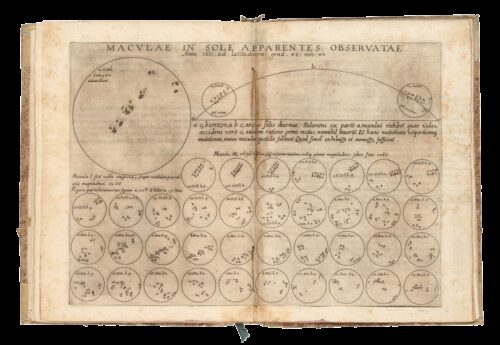

In the summer of 1610 Galileo and, shortly thereafter, the English astronomer Thomas Harriot, observed the Sun’s sunspots by means of an improved telescope.

Galileo made daily illustrations of the Sun’s image and took careful notes of the motion of the sunspots. He noticed that as the spots approached the edge of the Sun’s disk, they became narrower and slower, something which is consistent as if they were on the surface of a rotating sphere. From this Galileo concluded that the sun rotated on a fixed axis and that sunspots were features on the surface of the Sun and were not satellites of it.

Galileo (1564-1642). Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari e loro

accidenti. Rome: Giascomo Mascardi, 1613.

Scientific thinking is a tool for progress and the accumulation of knowledge. And the scientific method contains within itself the need to modify a theory when new evidence appears. Kepler quickly realized his mistake and, luckily for him, his slim volume did not appear to have achieved wide circulation.

The discovery of sunspots challenged the ancient notion of the Sun as a perfect celestial body and the immutability of the heavens. His claims were significant in undermining the traditional Aristotelian view that the Sun was unflawed and unmoving.

But seeing and deducing what observations mean may be the difference between seeing and a great discovery. Neither Kepler nor Galileo were the first to observe sunspots. The earliest apparent reference to them appears in the I Ching in ancient China. There were also reports from Islamic and European astronomers of sunspots in the early ninth century.

A year before Harriot and Galileo observed sunspots, both had decided to observe the Moon. Both saw the very same image of the Moon. But Galileo had a framework to inform what he saw and what he needed to see to support his intuition. His training in perspective and his knowledge about shadows projected by complicated objects, knowledge accumulated in the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, gave him this edge. Harriot was in London, then far behind Florence. Florence gave Galileo the edge. Harriot and Galileo’s observations of sunspots were a repeat of the Moon episode. Galileo’s visual imagination was again the crucial ingredient.